deliberate

one-off

confluence

wide-body plane

fuselage

escape chute

prolonged

dodge

incinerated

life-size dolls

final sweep

obstructed (their vision and breathing obstructed by the smoke)

stringent

deter

18 Minutes to Evacuate a Burning Plane: Success Story or Cautionary Tale?

Japan Airlines crash represents a puzzle for the airline industry

In its certification, Airbus was required to prove that its A350 aircraft can be evacuated in less than 90 seconds. In Tuesday’s collision in Japan, the last crew member escaped the aircraft after 18 minutes—but there were still no casualties.

The sizable discrepancy, for the moment, represents a puzzle for the industry: Does the safe and deliberate evacuation represent a triumph of new aircraft designs and improved procedures? Or was it a one-off, a fortunate confluence of events that doubles as a cautionary tale showing how difficult it is to quickly evacuate modern aircraft?

Aircraft safety and evacuation experts are applauding Japan Airlines’ cabin crew and passengers for escaping the burning wide-body plane without any loss of life before its fuselage collapsed. In doing so, they avoided what could have been one of the most deadly plane crashes in decades.

“Obviously it took a lot more than 90 seconds, but even though it did take longer, it was a very organized and a very orderly evacuation, and it was impressive,” said Anthony Brickhouse, an associate professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and director of its forensic crash lab. “This is a great case study.”

The 18-minute timeline begins at the moment of the airliner’s collision with a coast guard plane. It isn’t clear how long it took for the airliner to reach a standstill or when the formal evacuation order was given. Early passenger accounts suggest that the crew struggled for about three minutes to determine which exit doors were safe to open, and subsequently it took more than 10 minutes for all passengers and crew to leave the plane.

By comparison, in May 2019, a Russian-built and operated Sukhoi Superjet 100 was struck by lightning shortly after takeoff, forcing it to make an emergency landing. The aircraft hit the ground in the process, collapsing its landing gear, leaking fuel from the jet and causing a fire to erupt at the rear of the plane.

Videos of that incident showed passengers evacuating the aircraft for about 70 seconds before the plane was inescapable. Of 78 passengers and crew onboard, 37 survived, and the remaining—all seated toward the back of the aircraft where escape chutes weren’t available—died in the fire.

In 2020, a U.S. government watchdog published a report that reviewed accidents in the U.S. from 2009 to 2016. A range of factors led to those prolonged evacuations that took between roughly two and five minutes, the report found, including poor decision-making between cabin crew and pilots, and failures by passengers to pay attention during safety briefings, to leave all cabin bags behind, and to not use their cellphones during the evacuation.

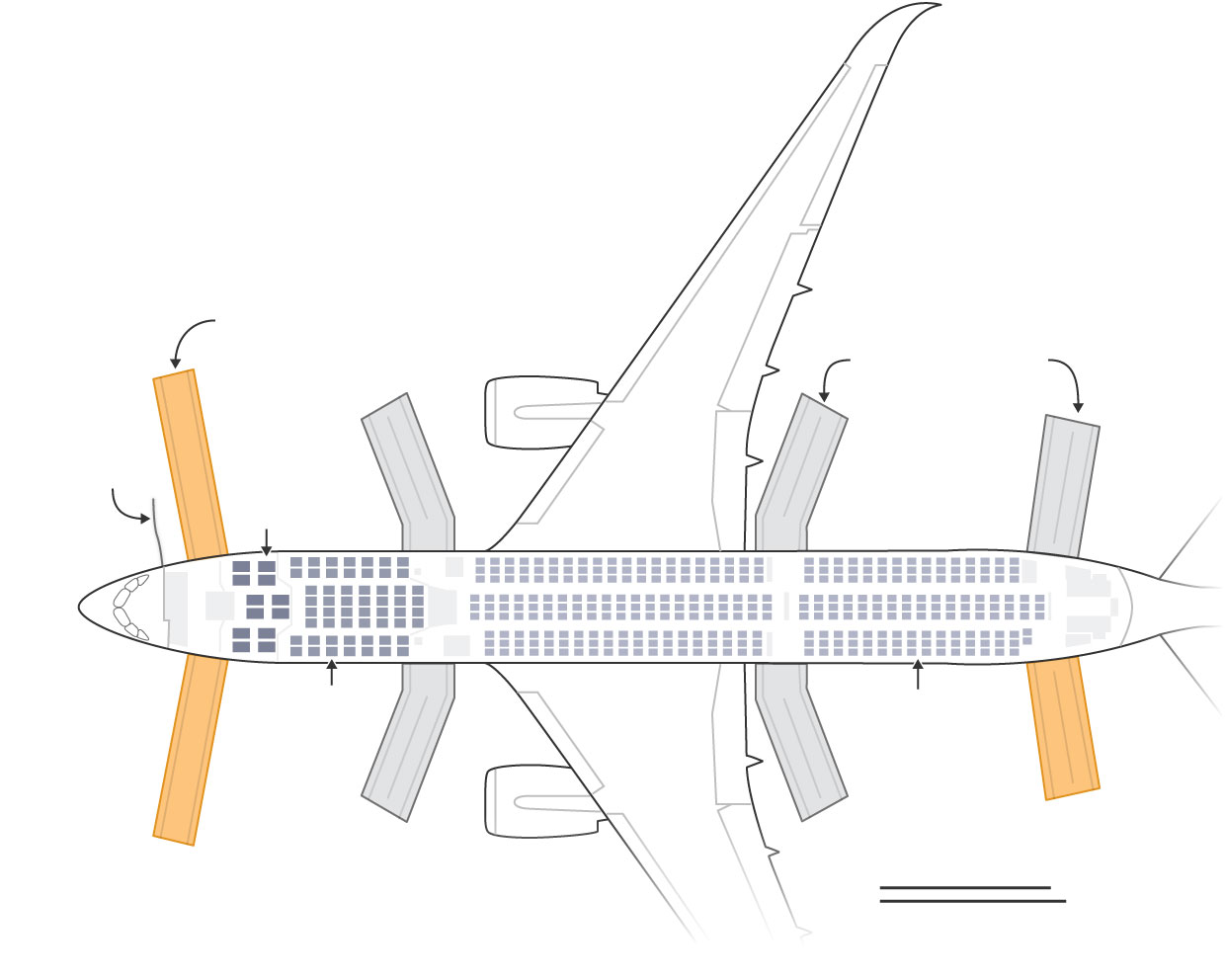

All 379 passengers and crew members safely evacuated the burning plane in under 20 minutes. Due to the fire, only three of the plane's eight exit doors were used in the evacuation, according to Japan Airlines.

The Japan Airlines crew appeared to dodge many, if not all of those pitfalls, but it is still not clear exactly why the evacuation took as long as it did.

“The 90 second rule is there for a reason, because that aircraft can obviously be incinerated in seconds,” said Sara Nelson, international president of the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, a union that represents cabin crew at several airlines. “The flight attendants appear to perform their jobs perfectly, but the question remains what was that configuration of the cabin? How close were the seats together? And who was on board?”

Current standards set by regulators including the Federal Aviation Administration and its European counterpart—which certifies all Airbus jets—require manufacturers to demonstrate that passengers can evacuate within 90 seconds under conditions that are meant to simulate real life.

The tests are an expensive and critical piece of the certification process. Airbus and Boeing recruit hundreds of volunteers to act as passengers on board with at least 40% of the participants required to be female, 35% over the age of 50 and a minimum 15% both female and over 50. Three life-size dolls must be carried to simulate real infants aged 2 years or younger.

Cabin luggage, blankets and pillows are also required to be strewn across the floor to create minor obstructions, and the lighting in the cabin must be dimmed to simulate the conditions of a catastrophic event. Only half the aircraft’s exits can be used—for the A350, that would mean four of eight—and passengers aren’t given a warning of when the evacuation is set to take place.

Tuesday’s evacuation in Tokyo looked very different. Only two of the plane’s exits at the front and one at the back were initially deemed safe—one less than the total used in the certification tests. The aircraft, typically used on Japan Airlines’ domestic routes, also had a high density configuration, capable of carrying 391 passengers, compared with the standard 300 to 350 seats.

The exit at the back was also likely available only temporarily before the flames had spread, leaving passengers near the back of the plane needing to reach the front two exits, their vision and breathing obstructed by the smoke that was rapidly filling the cabin.

The aircraft itself was tilted forward after the front landing gear collapsed making it difficult for passengers to navigate. The angle also hindered the steepness and therefore the speed of the aircraft’s front two chutes.

Cabin crew were left using megaphones or simply shouting when the public address system failed. On the pilot’s final sweep of the cabin, he also found some passengers who were still there, prolonging the full evacuation.

Part of Tuesday’s success was down to the design of the A350 and the stringent rules and measures used to deter the spread of flames across an aircraft, said Cristian Sutter, a cabin design specialist who led the team that developed the interiors for British Airways’ A350 fleet.

“The design, certification, materials and the lessons learned from previous accidents- what those do is buy you more time to evacuate,” Sutter said. “Those requirements bought enough time for an evacuation that was longer than the regulations require.”

“You can look at it two ways: Why did it take so long? 18 minutes is unacceptable; or: Even with 18 minutes taking too long, everyone onboard was saved,” Sutter said, adding that the pace a fire spreads across an aircraft is different in every incident. “In a different kind of accident, that time might not be there.”

Airbus said this week it would dispatch a team of specialists to assist the Japan Transport Safety Board in the investigation, adding that it will release more information when it is available and the company is authorized to release it.

Consumer groups and lawmakers have long been skeptical that the regulators’ requirements for certification tests can ensure speedy evacuations under real world conditions.

Planes have gotten bigger since such demonstrations were introduced following a 1965 crash in Salt Lake City. Passenger weight and girth have climbed in recent years, and seat spacing on many planes is tighter—developments some have argued regulators haven’t adequately considered.

The last update to evacuation requirements was in 2004, based largely on a 1991 collision between a Boeing 737 that was landing at Los Angeles International and a small twin turboprop that was waiting to take off. The crash killed 12 people aboard the smaller aircraft and 23 of the 89 crew and passengers on the 737. Most died due to smoke inhalation while waiting to exit.

In 2022, the FAA said a review of nearly 300 evacuations over the previous decade showed some areas for improvement, including recommending that safety announcements before takeoff and landing include instructions about leaving carry-on bags behind in an emergency. But the FAA also concluded that evacuation safety levels were high overall.

It also conducted its own evacuation trials to gauge the impact of different seat sizes and configurations and said it found little impact.

Lawmakers including Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D., Ill.) argue the FAA should take more real-life conditions into account in setting evacuation standards, and have proposed requiring the FAA to account for, among other things, passengers who are very young or very old, who have disabilities, or who don’t speak English. A modified version of the proposal is included in FAA reauthorization legislation.

The A350 is currently the biggest passenger jet available to buy new on the market. It typically carries between 300 and 350 passengers in a three-class configuration, but the version flown in Tuesday’s collision was higher density, capable of carrying up to 391. Its cabin runs 51 meters long, more than an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Tuesday’s collision was the first complete loss of the model by fire—or by any means—since its first flight in 2013.

Write to Benjamin Katz at ben.katz@wsj.com and Alison Sider at alison.sider@wsj.com

Copyright ©2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the January 5, 2024, print edition as 'Jet Evacuation Raises Questions About Safety-Certification Tests'.

'New Vocabularies' 카테고리의 다른 글

| I’m a Supercommuter. Here’s What It’s Really Like. (0) | 2024.01.09 |

|---|---|

| Elon Musk Has Used Illegal Drugs, Worrying Leaders at Tesla and SpaceX (0) | 2024.01.09 |

| A Dictator Can’t Bring Peace to Gaza (1) | 2024.01.04 |

| Read Harvard President Claudine Gay’s Letter to the University Community (0) | 2024.01.03 |

| Breaking Down the Spending at One of America’s Priciest Public Colleges (0) | 2023.12.29 |